The parts that make up the shoulder form a biomechanical relationship between different elements, which allow flexion, extension and abduction movements, among others. This leads to permanent injuries to the shoulder system, which can be treated in different ways.

Read on to find out what biomechanical movements are all about, the most common shoulder ailments and the non-invasive complementary treatments that are applied in this area. You'll also find a list of the best products to help relieve shoulder and neck pain. Take a look.

Parts and anatomy of the shoulder

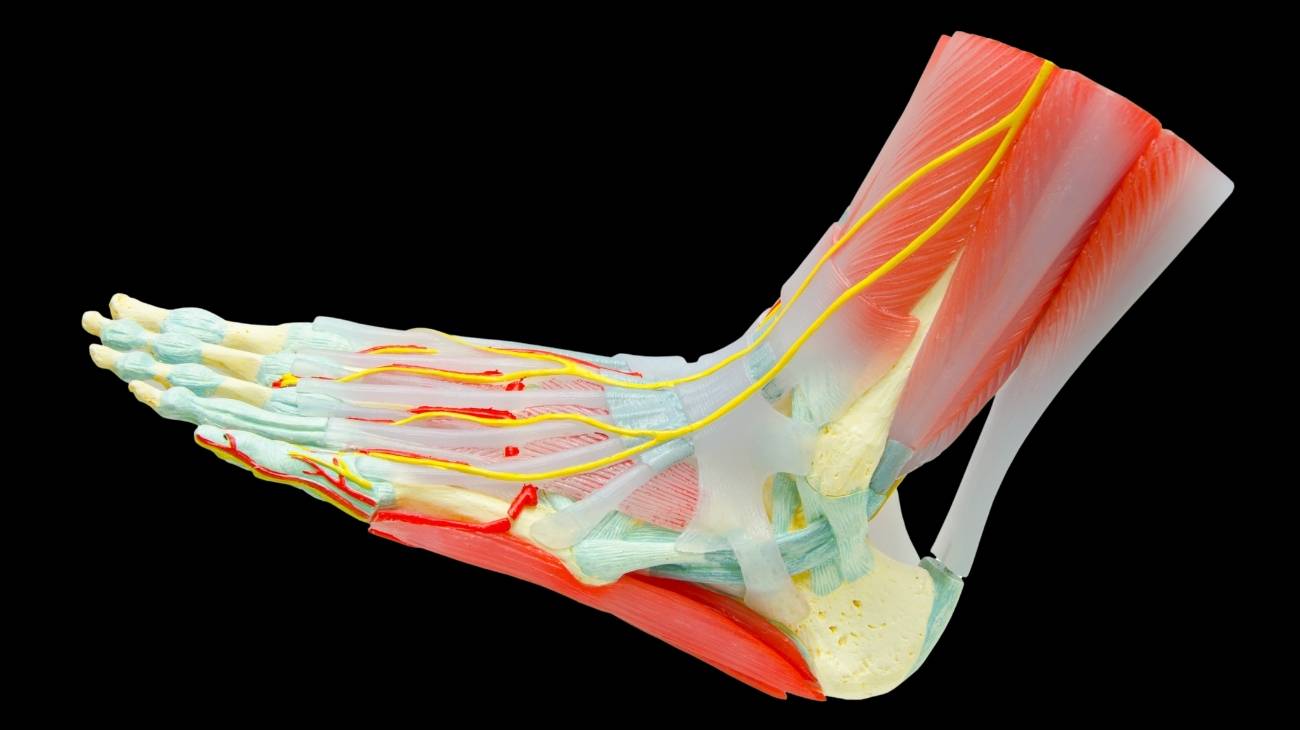

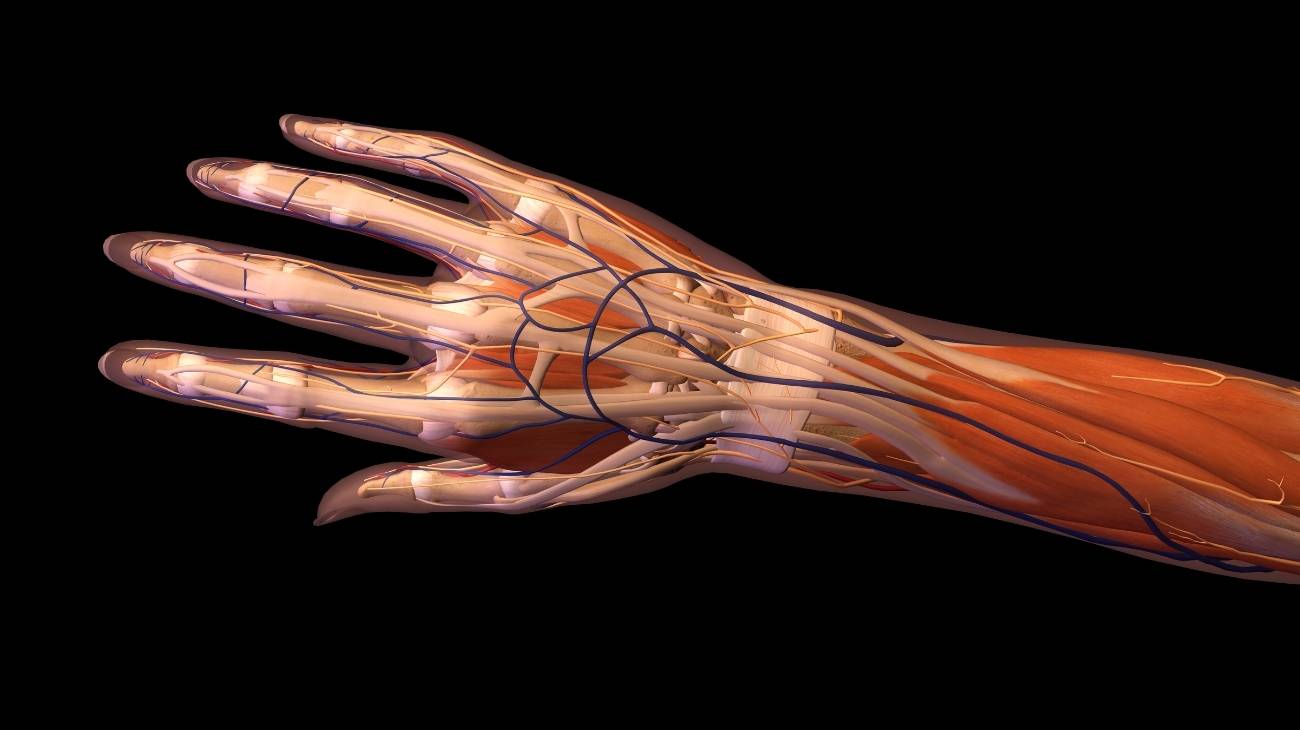

The shoulder complex is anatomically made up of the following:

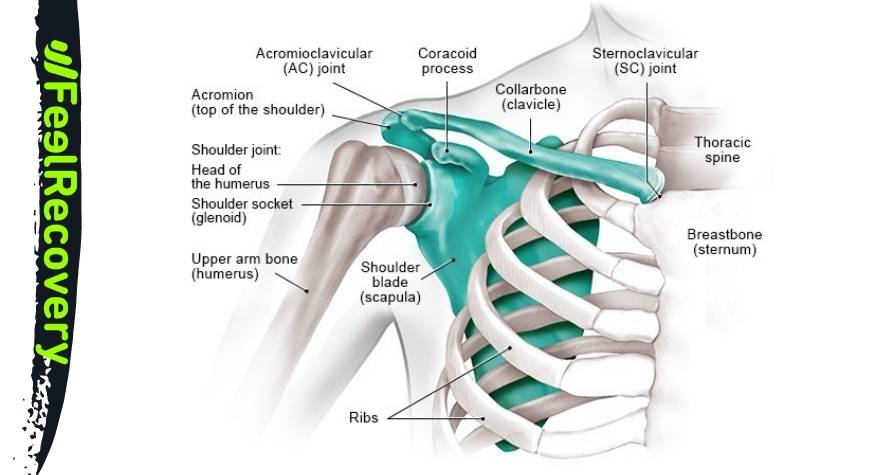

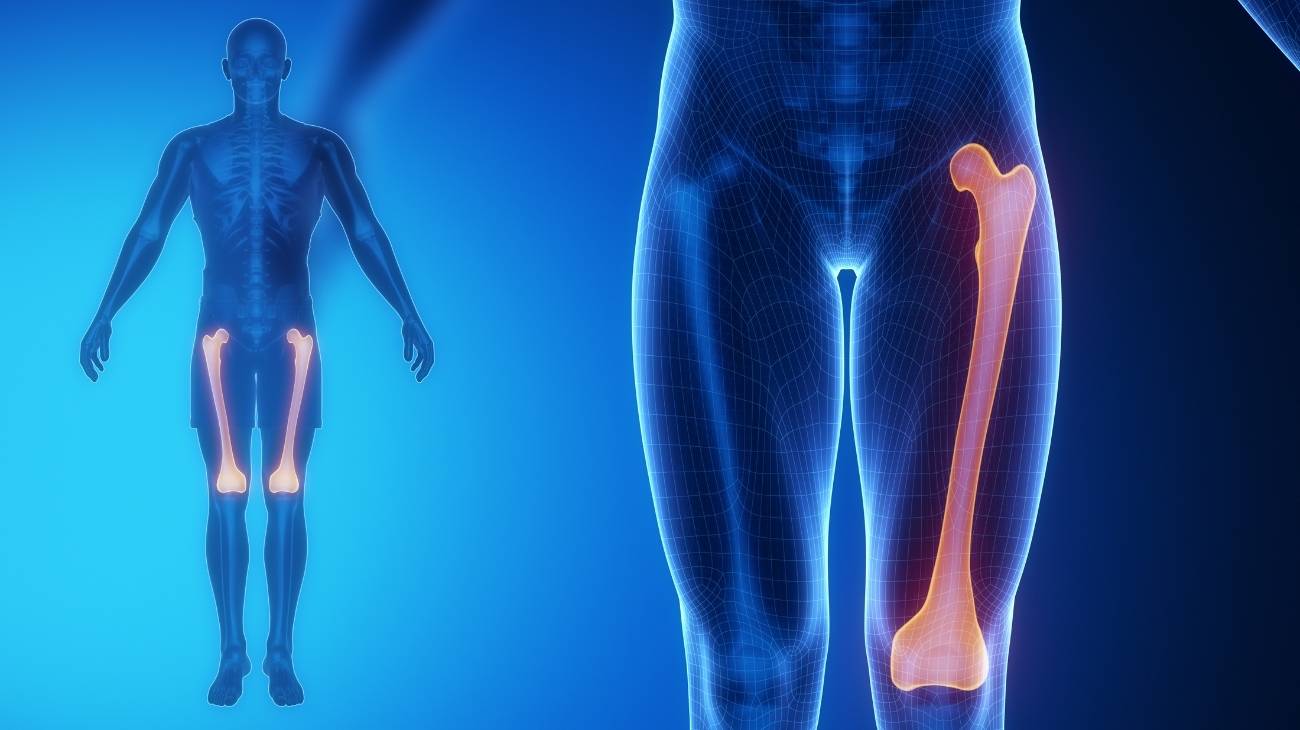

Bones and joints

The bones of the shoulder relate to the arm and the scapula, which belongs to the trunk. The clavicle is the main bony tissue of this joint, running along the sternum to the acromioclavicular ligament. After this ligament continues the acromion which, together with the coracoacromial ligament and the coracoid process, form the so-called shoulder fornix.

With regard to the shoulder joints, the following can be mentioned:

- The glenohumeral joint, which carries out the movements of the shoulder. That is, between the glenoid socket of the scapula and the head of the humerus is the hyaline cartilage, which cushions the movements of this part of the body.

- Another important joint is the subdeltoid joint: This articular body with the one mentioned in the previous point and connects the rotator cuff with the deltoid muscle.

- The non-anatomical scapulothoracic joint is involved in the movements of the thorax with the scapula at the top.

- While the acromioclavicular joint is responsible for moving the end of the clavicle with the acromion. This joint body is seated in a synovial bursa and surrounded by a ligament of the same name.

- Finally, the sternoclavicular joint joins the sternum to the clavicle on the inside. This allows adduction and abduction movements.

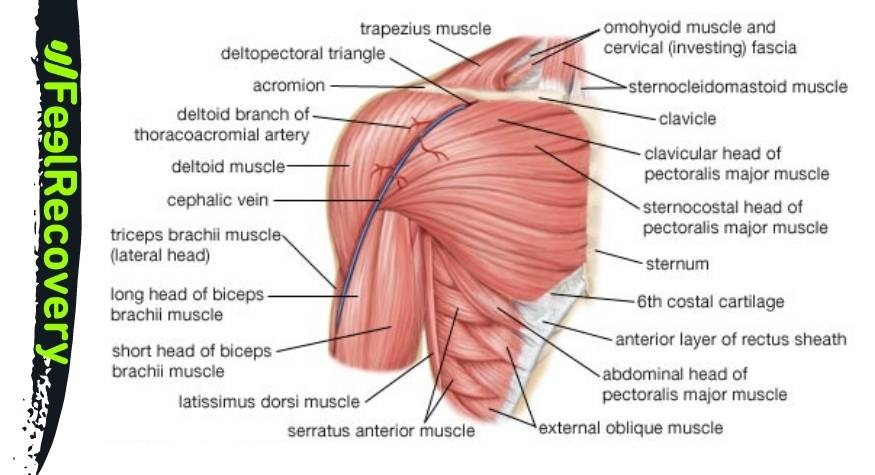

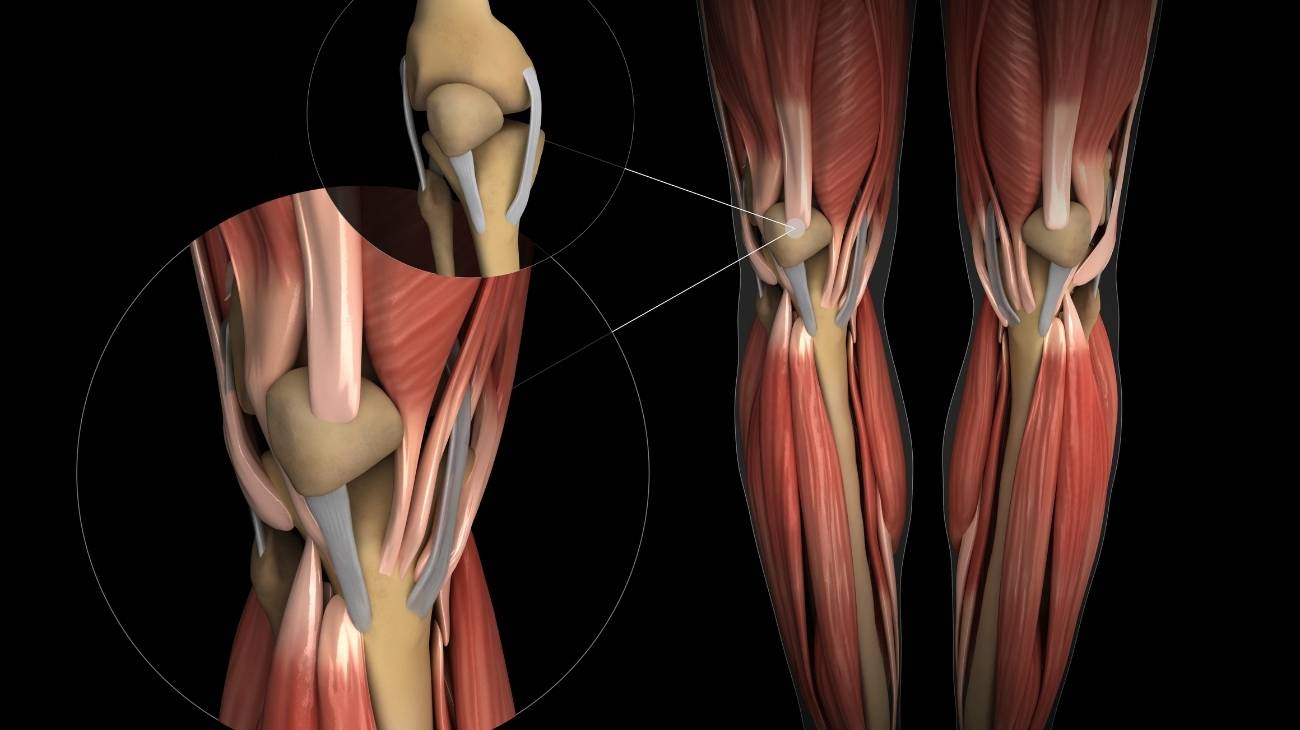

Muscles

The muscles that belong to the shoulder are:

- Supraspinatus: This muscle, together with the tendon of the same name, forms the rotator cuff of the shoulder. This muscle runs from the supraspinatus fossa of the scapula to the tip of the humerus. Its function is to stabilise the humerus bone and raise the arm.

- Subscapularis: It also covers the subscapular fossa and inserts on the lesser humeral tubercle. It is located in the anterior area of the scapula and is responsible for adducting the arm, maintaining shoulder stability and rotating the humerus.

- Roundus teres minor: It also has a rounded shape like the anterior muscle and its origin is similar to that of the roundus teres major, but the difference lies in its insertion, as it ends its course in the greater tubercle of the humerus. Lateral rotation of the arm is the main action of this tissue.

- Roundus major: It is possible to find this muscle on the back of the shoulder, as its job is to rotate and extend the arm. It has its origin in the scapula, in the inferior region, and is inserted in the number, precisely in the intertubercular groove.

- Deltoid: This shoulder muscle arises from the scapula, in the lower region of the crest, and inserts on the clavicle, on the edge of the acromion and on the spine of the scapula. They in turn converge on the humerus, inserting into the deltoid impression. Flexion, extension and abduction of the arm are its main biomechanical actions.

- Infraspinatus: This muscle extends from the infraspinous fossa to the epiphysis of the humerus or trochlea. Lateral rotation of the upper limbs is the main work of this soft tissue.

- Coracobrachialis: This muscle acts when the biomechanical movements of extension and flexion of the shoulder occur. The coracoid process is responsible for giving birth to this tissue, while the humeral diaphysis is the insertion zone.

- Pectoralis minor: This thin muscle has its insertion in the coracoid process and can therefore be considered an integral part of the muscular anatomy of the shoulder. Its task is to elevate the ribs during breathing.

- Trapezius: Although it is a muscle that can be considered as a muscle of the neck and trunk, its long course allows it to be mentioned as an integral part of the muscular tissues of the shoulder. Its action is to coordinate the movements of the scapula with the spine.

It is important to clarify that the infraspinatus, supraspinatus, subscapularis and teres minor muscles make up the anatomical group called the rotator cuff.

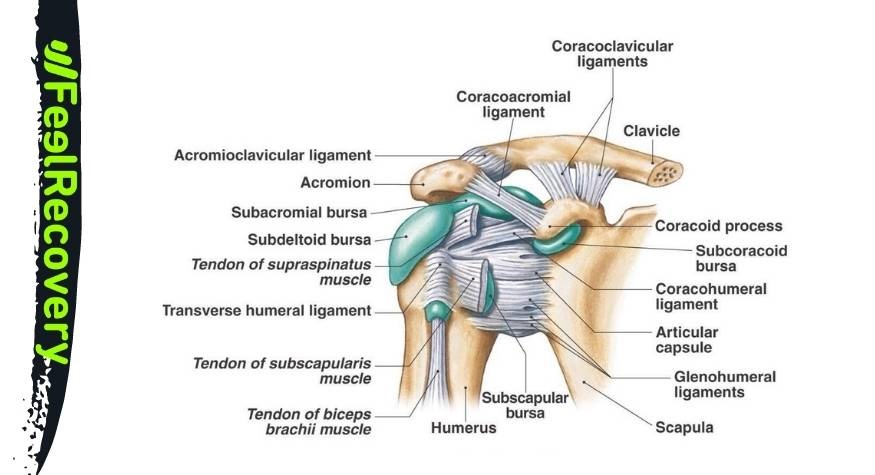

Ligaments

The following ligaments are present in the shoulder

- Coracoacromial: It is responsible for joining the clavicle to the coracoid process and its function is to limit the abduction movement of the shoulder. It can be divided into two sections, one called the conoid and the other called the trapezoid.

- Conoid: It is the first part of the anterior ligament, the acromion, at the medial part of its medial border, with the clavicle. It is related to the deltoid, trapezius and subclavian muscle.

- Trapezoid: As mentioned, this tissue is the second section of the coracoacromial ligament. It is up to 5 millimetres thick and runs from the coracoid process of the scapula to the underside of the clavicle.

- Acromioclavicular: Its route allows the clavicle to be joined to the acromion to maintain the work of the joint of the same name.

- Superior transverse of the scapula: This tissue joins the coracoid process with the medial end of the scapula. Its action, among other things, is to protect the suprascapular nerve.

- Glenohumeral: It can be divided into three sections, called superior, middle and inferior. This ligament joins the edges of the glenoid cavity to the medial bony protuberance of the humerus.

- Transverse humeral: The lesser and greater tubercles of the humerus are connected to the notch of the scapula by this ligament. Also known as coracohumeral.

- Coracoglenoid: This ligament extends from the coracoid process of the scapula to the glenoid socket, opposite the medial border of the scapula.

Best products for shoulder and neck pain relief

Bestseller

-

Microwave Heating Pad for Neck & Shoulder Pain Relief (Hearts)

$29.95 -

Microwave Heating Pad for Neck & Shoulder Pain Relief (Oxford)

$29.95 -

Microwave Heating Pad for Neck & Shoulder Pain Relief (Sport)

$29.95 -

Microwave Heating Pad for Neck Pain Relief (Hearts)

$24.95 -

Microwave Heating Pad for Neck Pain Relief (Oxford)

$24.95 -

Microwave Heating Pad for Neck Pain Relief (Sport)

$24.95 -

Microwaveable Heating Pad for Pain Relief (Hearts)

$24.95 -

Microwaveable Heating Pad for Pain Relief (Oxford)

$24.95 -

Microwaveable Heating Pad for Pain Relief (Sport)

$24.95

Biomechanics of the shoulder

The biomechanical movements that the shoulder can perform are as follows

- Flexion: This action occurs when the hand is raised forward, fully extending the arm. In this way the pectoralis major and deltoid muscles allow a 180° opening.

- Extension: By means of the teres major, latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major it is possible to bring the arm backwards with an amplitude of 50°.

- Adduction: It is possible to turn the arm 90° to the side of the body. In this way the upper limb joins the trunk at the hip. The latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major and subscapularis are the main muscles involved in this biomechanical movement.

- Abduction: This biomechanical act is the opposite of adduction. It consists of detaching the arm from the trunk until it reaches a maximum amplitude of 90°.

- Rotation: If the hand is moved outwards from the line of the elbow, an internal rotation of 90° is produced. On the other hand, if the hand flexes inward from the elbow to an opening not exceeding 90°, this movement is considered a biomechanical external rotation of the shoulder.

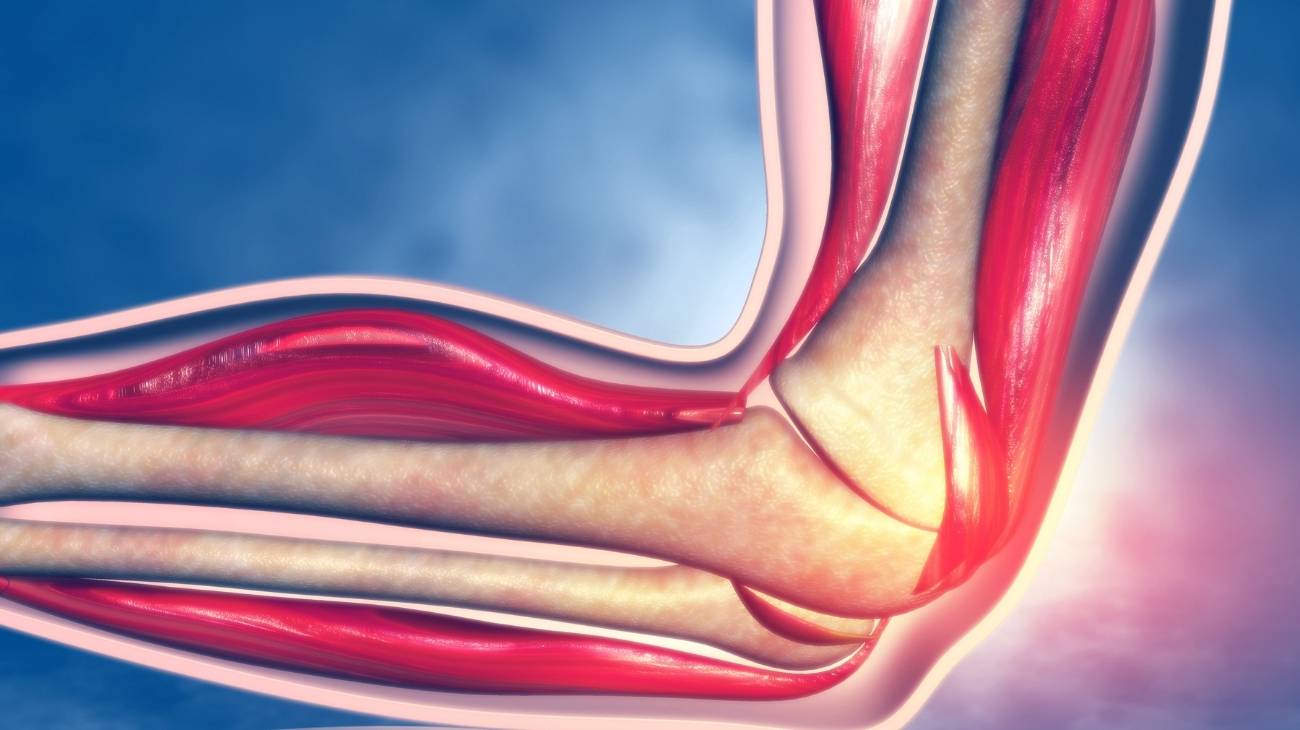

Most common shoulder injuries

It is possible to find a varied list of different contusions that can be caused to the shoulder due to the work this part of the body does in biomechanics. For this reason, we will show you below what the most common shoulder injuries are.

Types of shoulder injuries

The most common types of shoulder injuries and illnesses are:

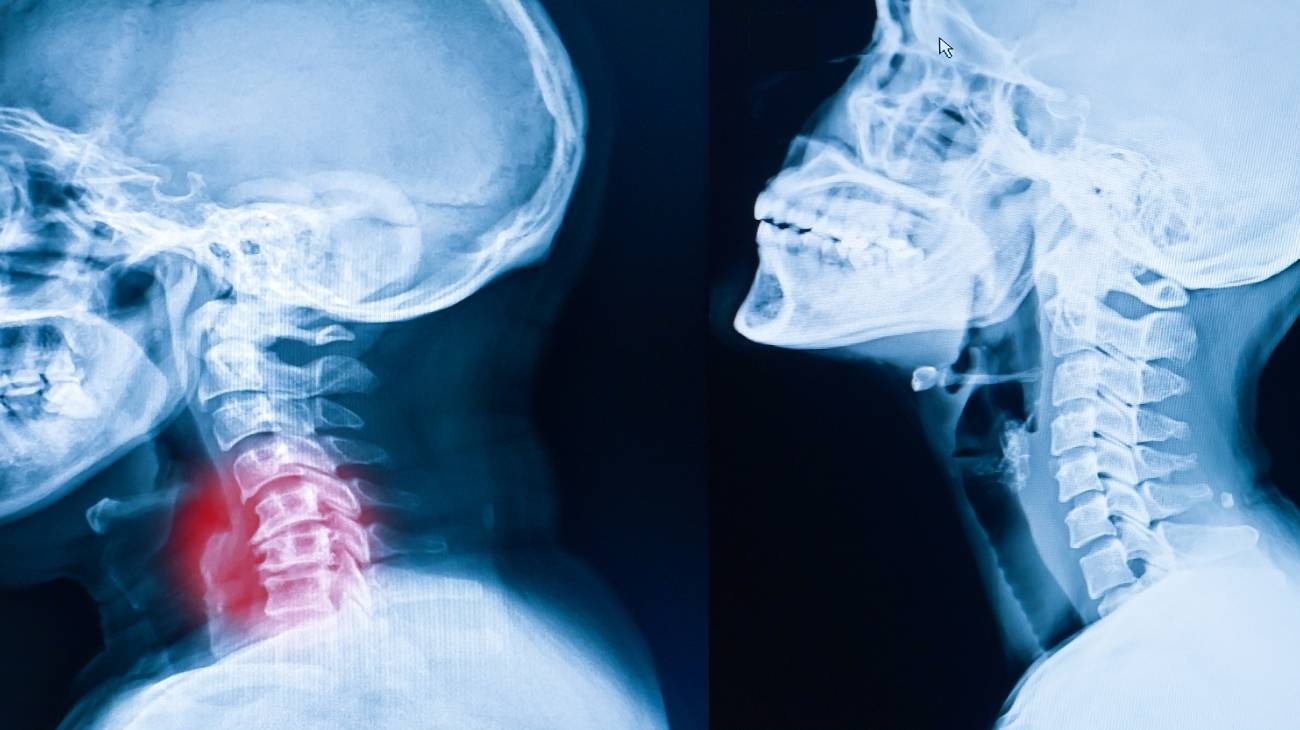

- Shoulder osteoarthritis: Deterioration of the articular cartilage and the development of osteophytes in the clavicle or coracoid process causes the shoulder joint to be impaired in its function. This can be caused by a variety of reasons, with age and trauma being the main risk factors.

- Shoulder bursitis: The subacromial bursa tends to become inflamed when there is excess fluid in a synovial sac. This causes inflammation in the affected area, pain and stiffness in the deltoid and supraspinatus. Recurrent blows and activities that place a great deal of stress on the shoulder lead to this condition.

- Shoulder fractures: While it is true that there are injuries to the acromion, the most common fractures occur in the clavicles, as it is a thin bone that is easily exposed to any blow or fall.

- Tendonitis in the shoulder: The ligaments of the coracoacromial group, the glenohumeral and the superior transverse of the scapula are prone to inflammation due to the accumulation of toxic substances and accumulate in these tissues. This results in pain and immobilisation of the shoulder, which can be cured with rest and complementary therapies.

- Tendonitis of the rotator cuff: Tendinitis occurs in this anatomical body when there is inflammation of the tendons located in this sector. This is caused by the inability of the blood to exchange nutrients with these fibres. Sudden activity and overexertion are also risk factors.

- Shoulder sprain: When a ligament in the shoulder is torn, it is known as a sprain. This can cause hypersensitivity, pain, swelling and redness. There are many causes of this injury, but the most common are sports activities and trauma.

- Shoulder strains: If the blood does not exchange gases and fluids with the muscles, metabolites are deposited in the muscle fibres. This causes involuntary contraction of the tissue, resulting in pain and stiffness. Sedentary lifestyles and repetitive movements without rest are the main causes of this ailment.

- Shoulder dislocation: Occurs when there is a separation, partial or complete, between the head of the humerus bone and the glenoid socket of the scapula. Depending on the type of slippage, it can be classified as a posterior or anterior shoulder dislocation. The reference point is the approach of the humerus to the acromion or coracoid process, respectively.

Sports shoulder injuries

The shoulder joint can also be injured during sports. Below you will find a complete list of the most common ailments in athletes

- Shoulder injuries in Yoga: Rotator cuff tears, acromioclavicular, trapezius and conoid tears are the most frequent injuries that occur in yoga. Although it is also possible to find contractures in the supraspinatus, teres minor and deltoid due to the demanding positions of this practice.

- Shoulder injuries in badminton: The continuous movements and excessive forces that the shoulder performs in this sport cause tendinitis and tearing of some tendons. It is rare to find breaks, the most frequent being those of the clavicles due to the falls the player suffers.

- Shoulder injuries in boxing: The blows provoked by the opponent can cause breaks in the acromion and clavicle fractures. In addition, muscle contractures of the trapezius and deltoid muscles are common. On the other hand, subacromial bursitis is recurrent in this sport.

- Shoulder and wrist injuries in cycling: Falls can fracture the acromion and clavicle, while the characteristic posture of the sport causes recurrent contractures of the pectoralis, subscapularis, infraspinatus, deltoid and teres contractures. Bursitis and tendonitis are also common in the sport.

- Shoulder injuries in Crossfit: Of the total number of injuries suffered by Crossfit athletes, 25% are to the shoulder. This is due to the great effort made by this joint to perform gymnastic movements and lifts. Tendinopathies are the most common ailments, especially in the rotator cuff.

- Shoulder injuries in climbing: Subacromial bursitis and tendinitis in the trapezius and conoid are the most frequent missions that these athletes have. It is also possible to find patients with dislocations and broken collarbones caused by accidents.

- Shoulder injuries in golf: Although the elbow is one of the most affected areas in this sport, this does not mean that the shoulder complex does not suffer injuries. The most common contusions are related to subacromial tendinopathies and rotator cuff tendinitis. Deltoid and teres contractures can occur.

- Shoulder injuries in football: The acromioclavicular joint is the most commonly accepted in the sport. Dislocations and sprains occur, but it is also possible to find players with broken collarbones and acromions. Muscle contractures are also common.

- Shoulder injuries in tennis: Glenohumeral dislocations and rotator cuff impingement, especially of the supraspinatus, are the most common injuries suffered by these athletes. Deltoid contractures are also frequent.

- Shoulder injuries in volleyball: Rotator cuff tendinitis and infraspinatus impingement are two ailments suffered by these athletes. On the other hand, the activity can also damage the teres minor and suprascapularis. The insertion of the capsule into the glenoid can become calcified or subacromial bursitis can occur.

Shoulder ailments and diseases

Among the most common and recurrent diseases and ailments suffered in the shoulder complex are the following:

Adhesive capsulitis

This disease is also known as "frozen shoulder". This is the inflammation that occurs in the joint, especially in the glenoid cavity with the head of the humerus. It is often found in people with diabetes and advanced age.

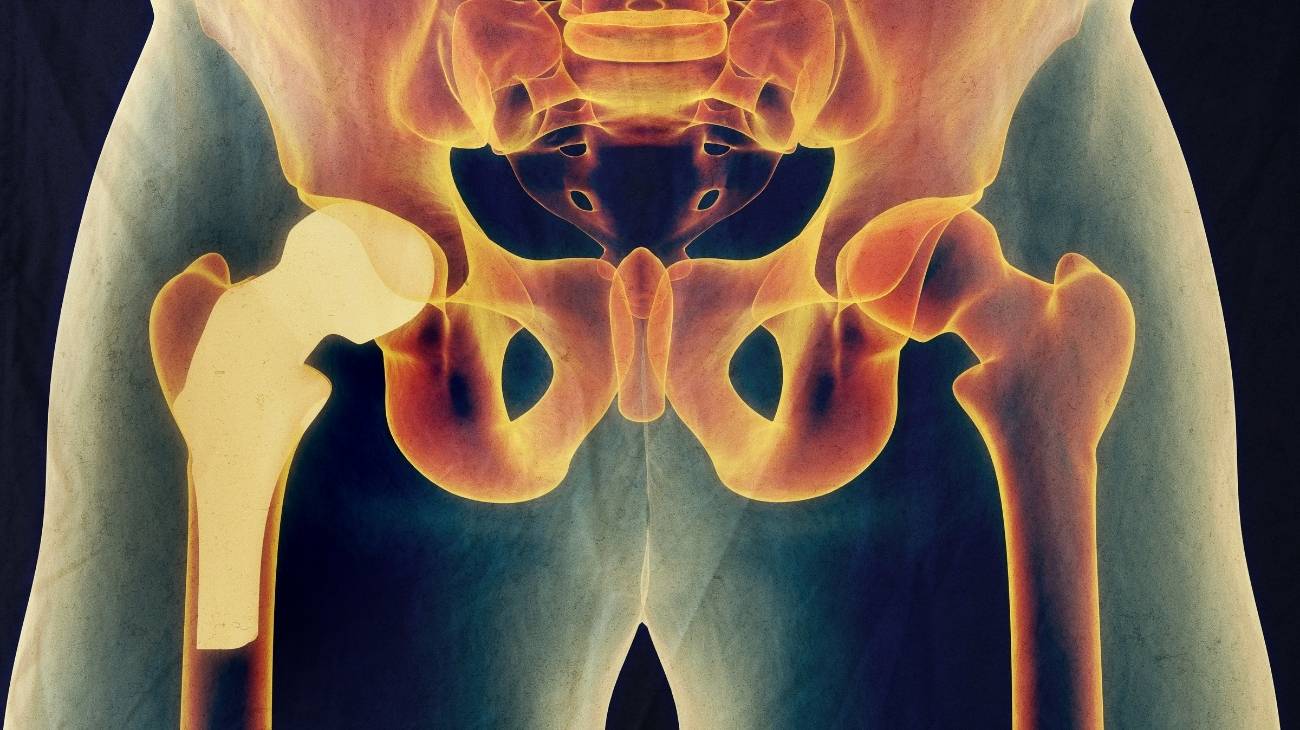

Dislocated shoulder

This condition occurs when the humerus, scapula and clavicle separate. In this way the humeral head is displaced from the glenoid cavity causing pain, immobility and inflammation. It can be caused by a variety of causes, the most common being trauma and demanding muscular activities.

Osteoporosis

This disease weakens the stiffness of the bones caused by a lack of blood supply to the bones. This results in clavicle and acromion fractures.

How can we relieve shoulder pain through complementary and non-invasive therapies?

We will show you below the different complementary therapies you can use to reduce shoulder pain and other symptoms. Take a look!

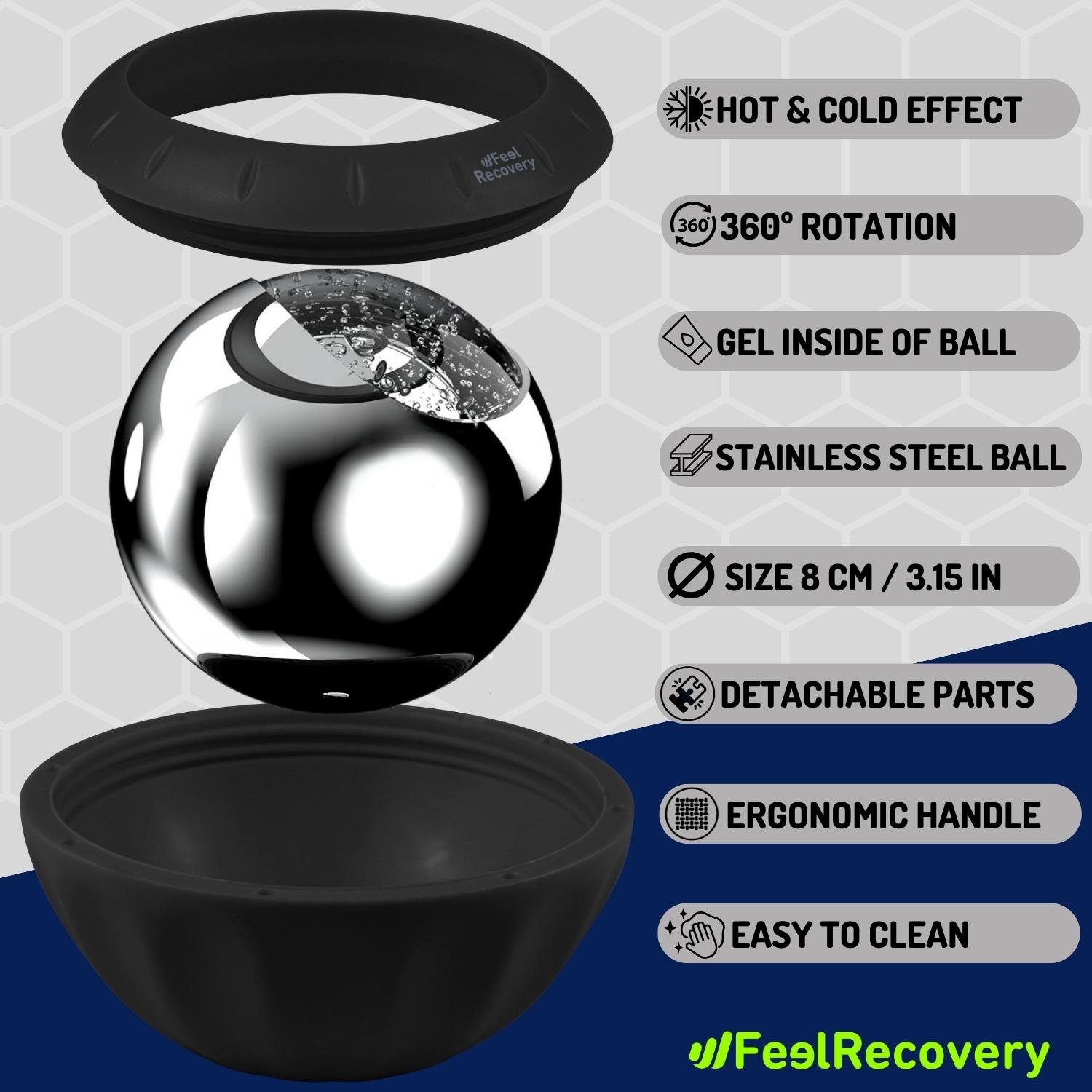

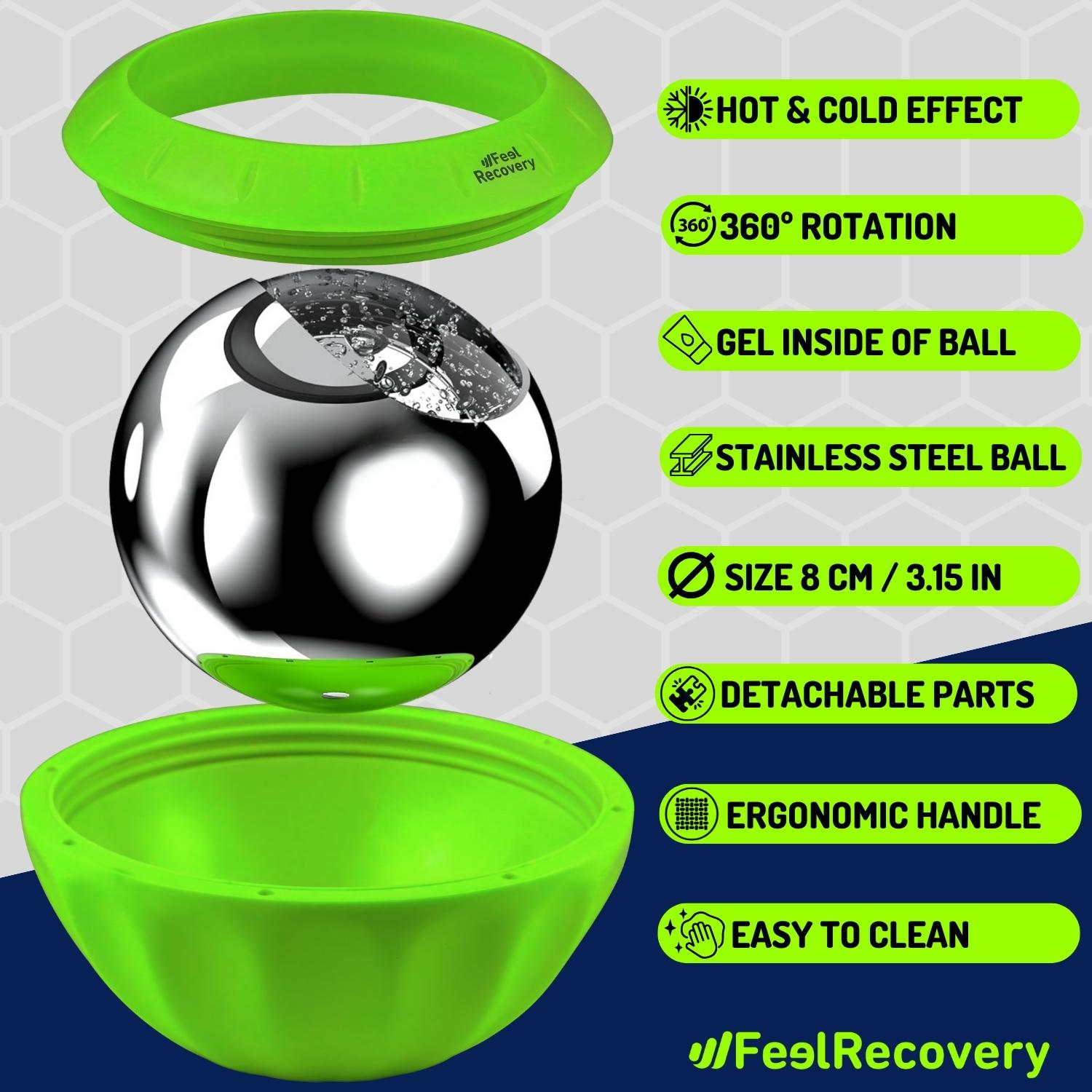

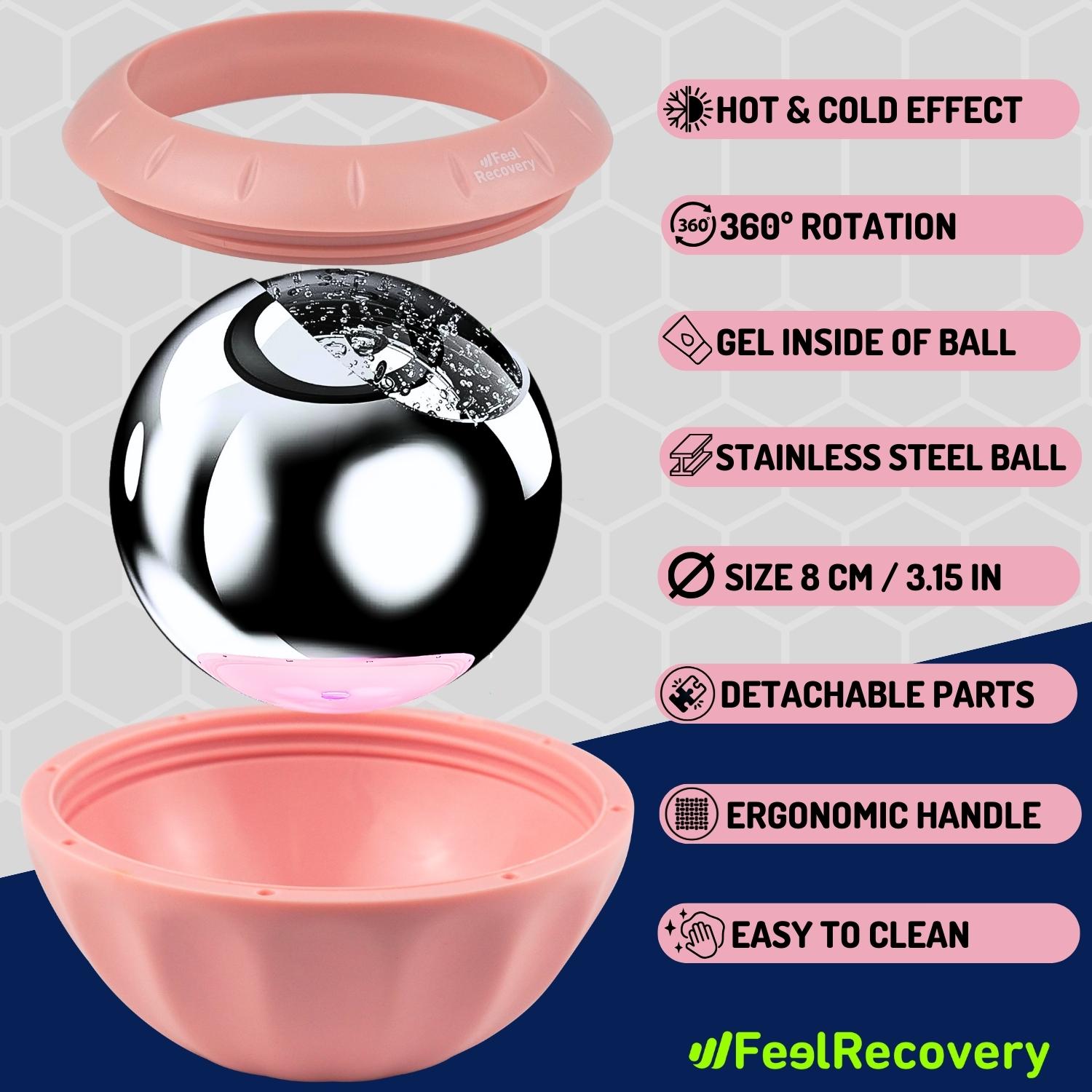

Heat and cold therapy

Treatment of the shoulder using heat and cold therapy involves using elements on the affected area to help reduce inflammation and pain. Different techniques can be used, but the most commonly used and least invasive are microwavable heat packs and cold packs with special gels and warm and cold baths. In some cases, natural plants are added to help improve blood circulation. This therapy should not exceed 20-25 minutes per session.

Compression therapy

Compression shoulder braces and elastic bandages are the most commonly used elements in this fixation therapy. It consists of keeping the entire shoulder complex as still as possible so that the muscles and other tissues are not strained with every movement. This helps to reduce pain and inflammation.

Massage therapy

To implement this treatment , it is ideal to use electric neck and shoulder massagers or percussion massage guns that promote the generation of internal heat in the muscles and ligaments of the shoulder complex. This allows the patient to regain mobility and pain free when performing everyday tasks.

Acupressure therapy

Restoring shoulder movement and reducing inflammation in the muscles and ligaments of the shoulder complex can be possible by massaging different areas of the body with controlled pressure. This oriental medicine stimulates the blood flow and the central nervous system. Manual massage rollers, massage balls and massage hooks can be used to generate these benefits, but it is necessary to consult a doctor before using them to avoid future complications.

Thermotherapy

Thermotherapy of the shoulder is very influential in reducing bursitis, tendinopathy and muscle contractures that occur in this complex. To obtain the benefits of heat, it is necessary the application of therapeutic massages by a professional or through products that provoke an ideal internal temperature in the tissues. For the latter case it is possible to choose between heat packs with hot and cold gels, thermal pillows for microwaves or manual massage rollers.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy on the shoulder helps to reduce the oedemas produced in this complex and also to improve the dilation of the capillary walls and to deflate the affected area in order to favour joint movements. To obtain these benefits, it is necessary to use cold chambers or the application (in a direct and non-invasive way) of cold-generating products. The latter include gel packs with compression straps, which can be applied to adults and children. It is advisable to consult a doctor before choosing any of these items.

Electrical muscle stimulation (EMS)

Muscle electrostimulation, or EMS, is a therapy that consists of stimulating muscle contractions through the use of electricity, so as to achieve an effect of activity and hypertrophy as in the gym, but without the need to go to any sports center. This means that you can put your muscles to work without leaving home.

Electrotherapy

This is a technique that seeks relief from pain and some physical ailments through the application of electrical and electromagnetic energy, among other variants, through the skin with the use of conductive pads called electrodes. It is a very safe type of therapy and must be applied by a physical therapist specialized in the manipulation of electricity to treat some kinds of ailments.

Myofascial release therapy

Also known as myofascial induction, this therapy consists of the application of manual massage to treat the shortening and tension generated in the myofascial tissue that connects the muscles to the bones and nerves. For this purpose, various massage techniques are used that focus on the so-called trigger points.

Percussion Massage Therapy

Vibration or percussion massages are precise, rhythmic and energetic strokes on the body to achieve relief from some annoying symptoms when muscle fibers are tightened, often by a high workload on them and that has left trigger points in the muscle fibers.

R.I.C.E Therapy

The R.I.C.E. therapy is the first and simplest of the treatment protocols for minor injuries. It appears in the sports field to deal with accidents involving acute injuries. For many years, it has been considered the most suitable for its speed and results.

Trigger points therapy

Myofascial pain points or trigger points are knots that are created in the deeper muscle tissues, causing intense pain. The pain does not always manifest itself right in the area where the point develops, but rather this pain is referred to nearby areas that seemingly do not appear to be related. In fact, it is estimated that more than 80% of the pain they cause manifests in other parts of the body.

Other effective alternative therapies

While it is true that the therapies mentioned so far are the most important, they are not the only ones that can be applied to treat shoulder complaints.

See below for other non-invasive treatments that can also be used:

- Natural remedies using plants: It is possible to reduce the symptoms of shoulder injuries by applying herbal teas or baths with lukewarm water for 15 to 20 minutes. Rosemary, linden, basil and laurel, among other plants, are used for this non-invasive technique.

- Acupuncture: In this oriental therapy there are psychological benefits for dealing with shoulder complaints. This is due to the mental harmony caused by the sessions when the central nervous system is stimulated.

- Kinesiotherapy: There are different exercises that are practised in this non-invasive therapy to improve shoulder injuries. This is done thanks to the intervention of a kinesiotherapist who stimulates the tissues in the affected area.

- Aromatherapy: This is a non-invasive treatment that uses aromas to provide the patient with mental harmony to support the pain and symptoms of shoulder injuries. Different objects are used to diffuse the scent of natural oils and plants.

- Osteopathy: This therapy seeks, by means of movements and massages, to reduce the symptoms caused by muscular and bone injuries in a natural way. It is important to clarify that this treatment must be supervised by a doctor to avoid serious consequences.

References

- Culham, E., & Peat, M. (1993). Functional anatomy of the shoulder complex. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 18(1), 342-350. https://www.jospt.org/doi/abs/10.2519/jospt.1993.18.1.342

- Halder, A. M., Itoi, E., & An, K. N. (2000). Anatomy and biomechanics of the shoulder. Orthopedic Clinics, 31(2), 159-176. https://www.orthopedic.theclinics.com/article/S0030-5898(05)70138-3/fulltext

- Terry, G. C., & Chopp, T. M. (2000). Functional anatomy of the shoulder. Journal of athletic training, 35(3), 248. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1323385/

- Dugas, J. R., Campbell, D. A., Warren, R. F., Robie, B. H., & Millett, P. J. (2002). Anatomy and dimensions of rotator cuff insertions. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery, 11(5), 498-503. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1058274602000642

- Van der Hoeven, H., & Kibler, W. B. (2006). Shoulder injuries in tennis players. British journal of sports medicine, 40(5), 435-440. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/40/5/435.abstract

- Quillen, D. A., Wuchner, M., & Hatch, R. L. (2004). Acute shoulder injuries. American Family Physician, 70(10), 1947-1954. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2004/1115/p1947.html

- Wilk, K. E., Obma, P., Simpson, C. D., Cain, E. L., Dugas, J., & Andrews, J. R. (2009). Shoulder injuries in the overhead athlete. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 39(2), 38-54. https://www.jospt.org/doi/full/10.2519/jospt.2009.2929

- Voight, M. L., & Thomson, B. C. (2000). The role of the scapula in the rehabilitation of shoulder injuries. Journal of athletic training, 35(3), 364. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1323398/

- Brox, J. I. (2003). Shoulder pain. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 17(1), 33-56. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1521694202001018

- Murphy, R. J., & Carr, A. J. (2010). Shoulder pain. BMJ clinical evidence, 2010. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3217726/