Knee injuries in rugby are among the most common rugby injuries. They are caused by excessive direct contact between players and opponents, among other risk factors. Knowing about them is important for the player to create strategies to avoid or reduce them.

In the following post we want to tell you about the most common types of knee injuries in rugby players, and the main first aid measures such as the RICE therapy. Take a look all the way to the end and find out all the details:

What are the most common types of knee injuries when playing rugby?

Rugby is a very violent sport where the ball carrier must be brought down by opponents through an action called tackling. During this movement, all kinds of high-impact collisions are generated that result in injuries, including knee injuries. The main risk factors are the speed of play and frequency of collisions and the rotational force exerted during a rapid change of direction.

Below, we want to tell you about the most common types of knee injuries when playing rugby, so that you are aware of them and can prevent them:

Knee ligament sprain

Knee sprain is the main knee injury in rugby players. In this condition, 1 to 4 of the ligaments that make up the knee may be partially or completely damaged.

In rugby, injury to the external lateral, internal lateral, posterior cruciate and anterior cruciate ligaments is mainly caused by sudden changes of direction at high speed, where the knee bends inwards. Also, when the foot is fixed to the ground and bending or twisting occurs.

Depending on its severity, it can be a grade I sprain, when an overstretching occurs with few broken fibres. In grade II, 50% of the ligament is ruptured, while in grade III the rupture is greater than 50%. The player will experience pain and inability to move, swelling, stiffness and gait instability.

Meniscal tear

It is very common that, during a game of rugby, the player makes sharp turns while the foot is fixed to the ground. This results in a tear in the C-shaped fibrocartilage structure or meniscus of the knee, either medially or laterally. The rugby player will experience acute pain, swelling, blockage of movement in the knee and popping. Although all symptoms depend on the type of meniscus injured and location.

Patellar tendonitis

This is a very common degenerative overuse injury in rugby players, caused by continuous use and constant repetitive movements in the lower limbs. It is also caused by jumping, landing or cutting abruptly at high speed. As a result, the patellar tendon stores and releases energy abruptly and repeatedly, without sufficient rest.

Over time, this leads to a remodelling and change in the mechanical properties of the tendon, indicating tendon injuries. The player will feel acute localised pain in the lower pole of the patella, and with increasing load on the knee extensors. A pathology that develops progressively, depending on the load tolerance of the tendon.

It consists of the gradual degeneration of the patellar tendon of the knee. It is characterised by pain just below the kneecap. It is considered an overuse injury, i.e. caused by repetitive overloading of the tendon by doing activities such as constant jumping and running.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

Patellofemoral pain syndrome is associated with overuse sports such as rugby. The aetiology of this pathology is associated with the wear and tear of the cartilage under the kneecap, becoming soft or rough. These changes are caused by the kneecap not being aligned correctly.

It is characterised by pain in the knee especially when bending the knee, jumping, using stairs or squatting. The knee may fail or give way unexpectedly, being unable to support the weight of the body. It may also cause popping during movement.

Fracture of the patella

Kneecap fractures are classified as transverse, vertical or longitudinal, according to the location of the fracture. These are generated when a direct blow is delivered to the anterior aspect of the patella or the player falls on the knee. Indirectly, but less frequently, when a violent traction movement of the quadriceps is generated, causing more damage than direct fractures.

Iliotibial band syndrome

Rugby is characterised as a sport that requires long and powerful runs, and this is the main risk factor for iliotibial band syndrome. It is characterised by pain and swelling on the outside of the knee. It is a progressive injury that limits the continuity of running, worsening over time, to the point of preventing sporting activity.

Other associated causes include the use of inadequate equipment, incorrect training, poor flexibility of the leg muscles, among others.

Best products for rugby knee injury recovery

Bestseller

-

2 Knee Compression Sleeve (Black/Gray)

£17,50 -

2 Knee Compression Sleeve (Green/Navy)

£17,50 -

2 Knee Compression Sleeve (Pink/Bordeaux)

£17,50 -

2 Patella Knee Strap (Black/Gray)

£12,95 -

2 Patella Knee Strap (Green/Navy)

£12,95 -

2 Patella Knee Strap (Pink/Bordeaux)

£12,95 -

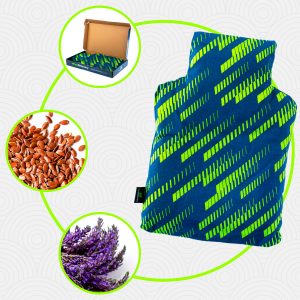

Microwave Wheat Bag for Back Pain Relief (Extra Large) (Hearts)

£25,50 -

Microwave Wheat Bag for Back Pain Relief (Extra Large) (Oxford)

£25,50 -

Microwave Wheat Bag for Back Pain Relief (Extra Large) (Sport)

£25,50 -

Microwaveable Wheat Bag for Pain Relief (Hearts)

£17,50 -

Microwaveable Wheat Bag for Pain Relief (Oxford)

£17,50 -

Microwaveable Wheat Bag for Pain Relief (Sport)

£17,50 -

Wheat Bag for Microwave Classic Bottle Shaped (Hearts)

£17,50 -

Wheat Bag for Microwave Classic Bottle Shaped (Oxford)

£17,50 -

Wheat Bag for Microwave Classic Bottle Shaped (Sport)

£17,50

How to apply the RICE therapy to treat knee injuries in rugby players?

In the event of a knee injury, the RICE therapy is the main first aid protocol applied to treat soft tissue injuries. These include knee sprains, strains and contusions. Its acronym stands for Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation, according to each of the phases that should be applied to relieve pain, reduce swelling and accelerate healing.

There is now a more up-to-date version of this protocol, but it is less well known. This is the PRICE therapy, which includes Protection as part of the initial process to prevent the injury from worsening. We will talk about this method below:

- Protection: The first step in protecting the knee and preventing the injury from worsening is to stop physical activity. However, as immobilisation is very relative, it is important to use crutches and knee braces.

- Rest: Rest will help speed up the healing process of the injury. Avoid moving the knee and weight bearing for at least the first 48 hours to reduce the inflammation and swelling process.

- Ice: Cryotherapy is especially indicated in cases of knee injuries to reduce pain and inflammation, due to the vasoconstrictor effect that promotes vasodilatation. This achieves an analgesic effect and decreases metabolism. It is recommended to apply cold gel compresses to the knee in 5-10 minute sessions, at 1-2 hour intervals, for at least 3 days in a row.

- Compression: Elastic bandages or kneepads are the ideal option to apply compression to the knee without putting too much pressure on it. This will help reduce swelling.

- Elevation: Use a pillow while lying down to raise your knee above the level of your heart. This helps to reduce swelling and pain. However, this limb must be raised 15 to 25 cm above the heart for full descent to occur.

References

- Dallalana, R. J., Brooks, J. H., Kemp, S. P., & Williams, A. M. (2007). The epidemiology of knee injuries in English professional rugby union. The American journal of sports medicine, 35(5), 818-830. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0363546506296738

- Bourne, M. N., Opar, D. A., Williams, M. D., & Shield, A. J. (2015). Eccentric knee flexor strength and risk of hamstring injuries in rugby union: a prospective study. The American journal of sports medicine, 43(11), 2663-2670. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0363546515599633

- Levy, A. S., Wetzler, M. J., Lewars, M., & Laughlin, W. (1997). Knee injuries in women collegiate rugby players. The American journal of sports medicine, 25(3), 360-362. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/036354659702500315

- Riyami, M., & Rolf, C. (2009). Evaluation of microfracture of traumatic chondral injuries to the knee in professional football and rugby players. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, 4, 1-8. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1749-799X-4-13

- Akins, J. S., Longo, P. F., Bertoni, M., Clark, N. C., Sell, T. C., Galanti, G., & Lephart, S. M. (2013). Postural stability and isokinetic strength do not predict knee valgus angle during single-leg drop-landing or single-leg squat in elite male rugby union players. Isokinetics and Exercise Science, 21(1), 37-46. https://content.iospress.com/articles/isokinetics-and-exercise-science/ies00469

- Kaplan, K. M., Goodwillie, A., Strauss, E. J., & Rosen, J. E. (2008). Rugby injuries. Bulletin of the NYU hospital for joint diseases, 66(2), 86-93. https://www.safetylit.org/citations/index.php?fuseaction=citations.viewdetails&citationIds[]=citjournalarticle_88090_11

- Freitag, A., Kirkwood, G., Scharer, S., Ofori-Asenso, R., & Pollock, A. M. (2015). Systematic review of rugby injuries in children and adolescents under 21 years. British journal of sports medicine, 49(8), 511-519. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/49/8/511.short

- Bottini, E., Poggi, E. J. T., Luzuriaga, F., & Secin, F. P. (2000). Incidence and nature of the most common rugby injuries sustained in Argentina (1991–1997). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 34(2), 94-97. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/34/2/94.short

- Gibbs, N. (1994). Common rugby league injuries: recommendations for treatment and preventative measures. Sports Medicine, 18, 438-450. https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/00007256-199418060-00007

- Carson, J. D., Roberts, M. A., & White, A. L. (1999). The epidemiology of women's rugby injuries. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 9(2), 75-78. https://journals.lww.com/cjsportsmed/abstract/1999/04000/the_epidemiology_of_women_s_rugby_injuries.6.aspx