Rugby is characterised by fast movements, combined with contact and fighting. This makes it a sport discipline with a high potential to trigger injuries.

Some types of tackles, especially those with a high inertial load on the head and neck, are triggers for sports neck injuries in rugby. If you want to know which are the most common ones and how to treat them with the RICE therapy, have a look at the following.

What are the most common types of neck injuries when playing rugby?

The position and physical characteristics of each player largely determine the decrease in tackling. The fewer the number of tackles, the lower the chance of injury. Among other aspects, the psychomotor speed, visual memory and reaction times of each player also play a role. We cannot ignore the time spent playing rugby, as this is a factor in overuse injuries caused by improper repetitive movements. Especially during flexion, external and internal rotation, circumduction and extension.

Below, we will discuss the most common neck injuries in rugby so that you can understand how they occur and avoid them by developing prevention strategies:

Cervical fracture

A cervical fracture is one of the most serious injuries sustained during a game of rugby. Depending on the severity of the injury, the player could make a full recovery or, in a less encouraging situation, die. Statistical studies show that the most frequent injury has been during hyperflexion of the cervical spine. This injury is caused by fracture and dislocation of C4-C5 or C5-C6.

Scrum and tackles are the contact situations that are the main risk factors for neck injuries from playing rugby. This is especially true on very hard surfaces, and the player lacks the physical conditioning and practice to comply with the physical contact phases of this sporting discipline.

Cervical dislocation

A cervical dislocation or dislocation occurs when the joint becomes dislocated and does not return to its normal position. As we know, the cervical spine is that bony part of the neck which is made up of 7 vertebrae. Neck dislocations in rugby are caused by high impact trauma and collisions through violent contact.

This can occur with or without a fracture. But, in either case it will cause acute local pain and pinching of nerves associated with the upper limbs. In the worst case, it can cause significant impairment such as paralysis and even death.

Neck strain

In a quick or forced turn during a rugby match, the neck may bend more than it should, causing a neck strain. As a result, muscles, tendons, nerves and other tissues in the neck are stretched or strained. Some tackles cause sudden impacts between players that will force the neck to stretch very quickly beyond normal. Subsequently, it may snap backwards from the force generated, causing whiplash.

The player should stop all activity, as this type of injury worsens with movement. The pain may take a day to appear, and may even spread to the shoulders and upper back. You may also experience dizziness, fatigue, ringing in the ears, and numbness in the hands and arms.

Cervical facet syndrome

The etiology of cervical facet syndrome is presumed to lie in injury to posterior elements of the spine. Most of the time, it is related to whiplash or degenerative injuries resulting from repetitive movements, stiffness, trauma, among others. It is also associated with the rotation and hyperextension required by some situations and movements during a rugby match. Although this type of pain does not radiate, if it does, it will radiate towards the thigh and buttocks.

Brachial plexus injury

No one thinks of neck injuries when playing rugby, but, in a sport that demands fighting and repetitive movements, the force exerted during phases of play may increase the normal angle between the neck and shoulders. It can also be caused by a blow to the neck or shoulder.

Consequently, there will be overstretching and possible tearing. This type of injury can also tear the roots of the brachial plexus. This will result in nerve damage, loss of feeling and loss of strength in the muscles. In the worst case, it can lead to permanent paralysis of the arms.

Cervical disc injuries

Playing rugby carries a high risk of developing herniated discs. This degenerative pathology is caused by wear and tear of the structures that form and surround the disc. Although there will be no rupture, a tear may occur.

Some studies affirm that, when forming the scrum in a rugby match, especially the position in the front row, represents a great risk factor. This increases the possibility of trauma or injury to the neck, which will eventually cause this wear and tear. Symptoms experienced by the athlete include pain, numbness, tingling and weakness in muscles.

Best products for recovery from neck injuries in rugby

Bestseller

-

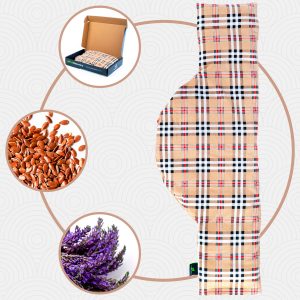

Microwave Wheat Bag for Neck & Shoulder Pain Relief (Hearts)

£24,95 -

Microwave Wheat Bag for Neck & Shoulder Pain Relief (Oxford)

£24,95 -

Microwave Wheat Bag for Neck & Shoulder Pain Relief (Sport)

£24,95 -

Microwave Wheat Bag for Neck Pain Relief (Hearts)

£20,95 -

Microwave Wheat Bag for Neck Pain Relief (Oxford)

£20,95 -

Microwave Wheat Bag for Neck Pain Relief (Sport)

£20,95 -

Microwaveable Wheat Bag for Pain Relief (Hearts)

£20,95 -

Microwaveable Wheat Bag for Pain Relief (Oxford)

£20,95

How to apply the RICE therapy to treat neck injuries in rugby players?

The RICE therapy is a first aid protocol indicated for most minor injuries, such as sprains, muscle strain, among others. Its effectiveness in reducing inflammation, relieving pain and speeding up recovery is due to the fulfilment of a set of phases.

Below, we will tell you how to apply the PRICE therapy to treat neck injuries in rugby:

- Protection: The initial phase of this method corresponds to the protection of the injured area to prevent it from worsening. The athlete should suspend all activity and movement of the neck. To help, a vertical collar can be worn to immobilise the neck, preventing rotational and flexion and extension movements, protecting the spinal region.

- Rest: Rest should be combined with the initial phase of protection, to contribute to tissue healing after the trauma. In addition to avoiding movement, the person should rest for at least two days, and depending on the severity of the injury, resume activity gently.

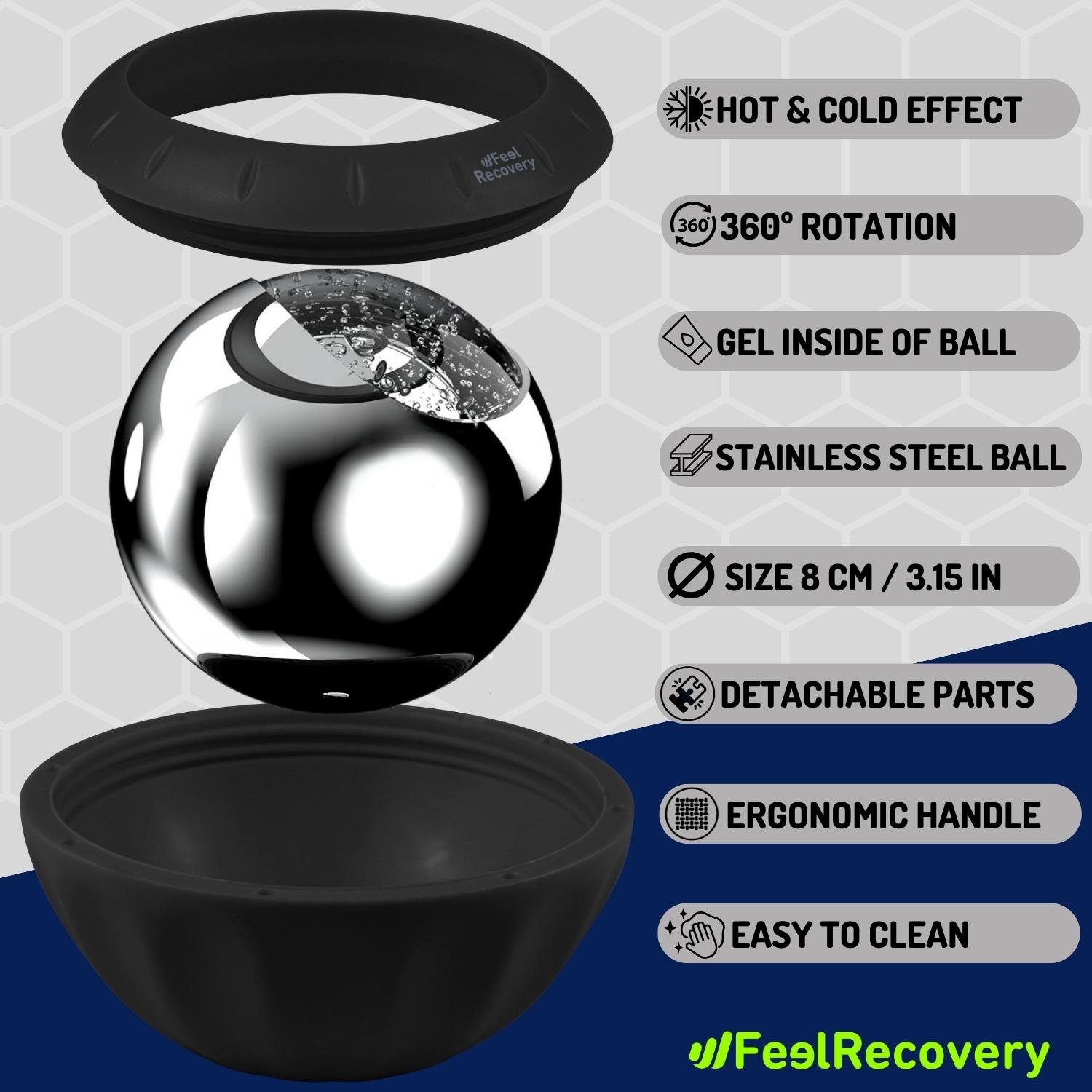

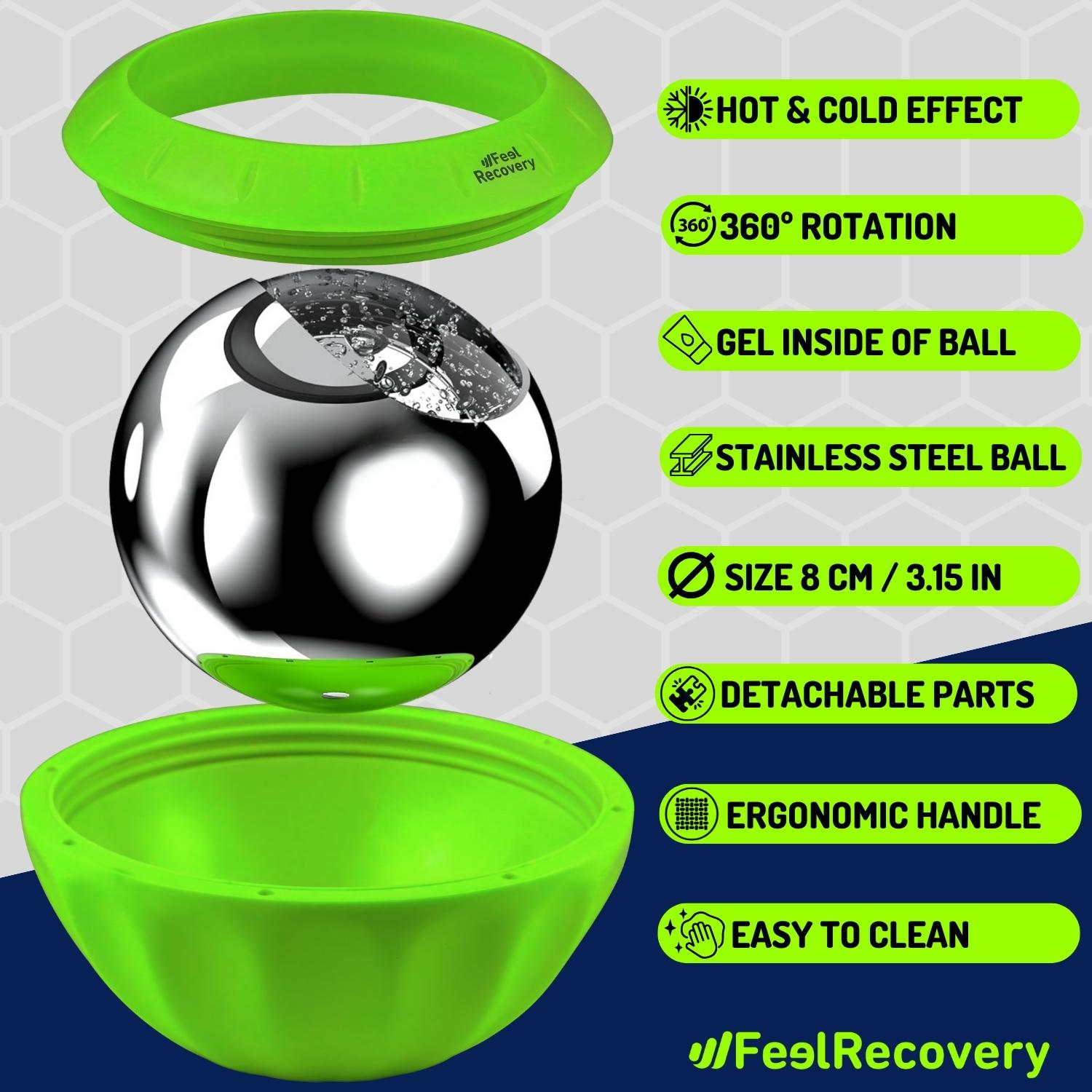

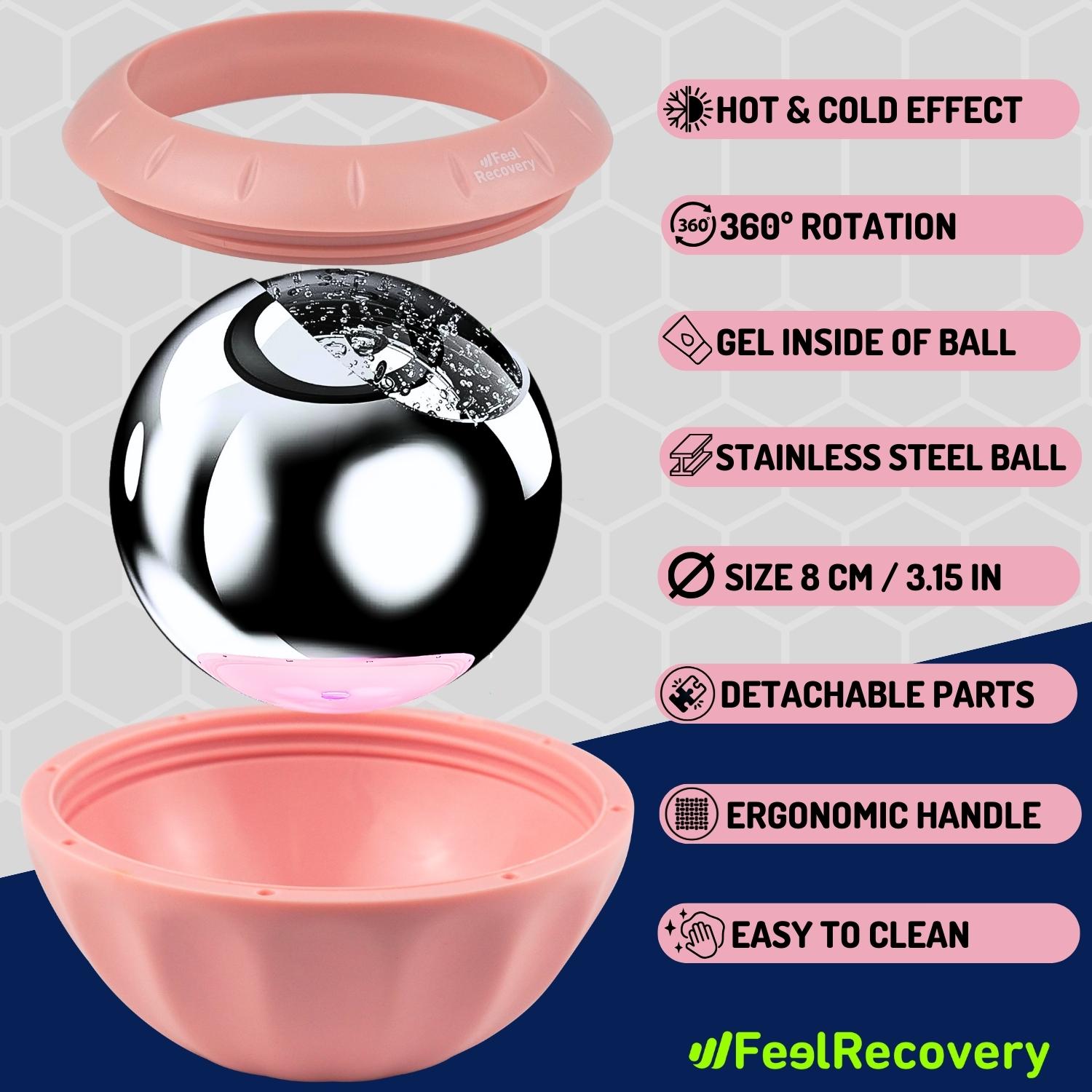

- Ice: In this phase it is recommended to apply ice to reduce oedema due to vasoconstriction. You can use filled gel packs to apply cold for a maximum of 15 minutes, at 1 hour intervals, for three days.

- Compression: This phase consists of compressing the injured area using an elastic bandage, without pressing too hard. This is to limit the expansion of the skin. However, this phase is intended for injuries to the upper and lower extremities. As the neck is involved, we will omit this phase in this case.

- Elevation: As with compression, elevation should be omitted for this part of the body. However, in the case of lower and upper extremity injuries, the area should be elevated to the level of the heart to aid venous return, reduce pain and prevent swelling.

References

- McIntosh, A. S., McCrory, P., Finch, C. F., & Wolfe, R. (2010). Head, face and neck injury in youth rugby: incidence and risk factors. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(3), 188-193. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/44/3/188.short

- Gianotti, S., Hume, P. A., Hopkins, W. G., Harawira, J., & Truman, R. (2008). Interim evaluation of the effect of a new scrum law on neck and back injuries in rugby union. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(6), 427-430. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/42/6/427.short

- MacLean, J. G., & Hutchison, J. D. (2012). Serious neck injuries in U19 rugby union players: an audit of admissions to spinal injury units in Great Britain and Ireland. British journal of sports medicine, 46(8), 591-594. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/46/8/591.short

- Wetzler, M. J., Akpata, T., Laughlin, W., & Levy, A. S. (1998). Occurrence of cervical spine injuries during the rugby scrum. The American journal of sports medicine, 26(2), 177-180. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/03635465980260020501

- Bohu, Y., Julia, M., Bagate, C., Peyrin, J. C., Colonna, J. P., Thoreux, P., & Pascal-Moussellard, H. (2009). Declining incidence of catastrophic cervical spine injuries in French rugby: 1996-2006. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 37(2), 319-323. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0363546508325926

- Quarrie, K. L., & Hopkins, W. G. (2008). Tackle injuries in professional rugby union. The American journal of sports medicine, 36(9), 1705-1716. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0363546508316768

- Quarrie, K. L., Cantu, R. C., & Chalmers, D. J. (2002). Rugby union injuries to the cervical spine and spinal cord. Sports Medicine, 32, 633-653. https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/00007256-200232100-00003

- Brooks, J. H., Fuller, C. W., Kemp, S. P., & Reddin, D. B. (2006). Incidence, risk, and prevention of hamstring muscle injuries in professional rugby union. The American journal of sports medicine, 34(8), 1297-1306. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0363546505286022

- Silver, J. R., & Stewart, D. (1994). The prevention of spinal injuries in rugby football. Spinal Cord, 32(7), 442-453. https://www.nature.com/articles/sc199471

- Newton, D., England, M., Doll, H., & Gardner, B. P. (2011). The case for early treatment of dislocations of the cervical spine with cord involvement sustained playing rugby. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British volume, 93(12), 1646-1652. https://boneandjoint.org.uk/article/10.1302/0301-620X.93B12.27048