The calves are one of the parts of the body most used in running, so their muscles and tendons must be strong and resistant to withstand all the effort required in a race, whether it is a hobby or a competition.

When the calf muscles are weak, the runner is exposed to various injuries which we are going to explain in this article, as well as showing you how to treat them with the RICE first aid therapy in the most effective way possible.

What are the most common types of calf injuries when running?

Calf injuries are not very common in running, as it is actually the section of the lower body that is least stressed when running, as most of the stress is generated by both the quadriceps and hamstrings. In disciplines such as 100m, 200m and 400m sprints, the calves are more likely to suffer.

Here are some of the most common calf injuries you may experience as a runner:

Calf contracture

Depending on the runner's running technique, the calves will be used more or less. For example, if the runner has a stride that relies on the toe of the foot to propel the stride, he or she will undoubtedly be activating these muscles constantly. This continuous use during a long run causes them to be overloaded with stress, causing them to start contracting involuntarily at a certain point.

This muscle contraction is a clear indication that the muscle is reaching its limit and may even tear if it continues to be strained. The runner will feel a slight pain in the calf that will force him to stop for a moment, and although it can be solved with a quick stretch, the recommendation is to stop or reduce the intensity of jogging to avoid a possible muscle tear.

Calf muscle tear

As a muscle accumulates stress from constant use, its fibres weaken. This can be aggravated if the runner is not in the habit of warming up properly before starting the high-impact activity, and above all, if the muscle is constantly pushed to the limit without proper rest the days before or without proper physical preparation.

The calf muscles are not exactly the most common muscles for a runner to tear, but the probability is latent as it is a sport in which the lower body is so demanding. When it happens, you will feel a sharp pain that will force you to stop jogging immediately, so much so that even trying to walk will be very painful. If this muscle pull occurs in a sprint race, a partial or complete tear of the muscle is more likely to occur.

Tibial fracture

The tibia is the bone at the front of the calf. It is one of the longest after the femur and also one of the strongest. However, it is usually the one that is subjected to the most stress because it bears the brunt of the impacts generated by running, which causes it to accumulate stress progressively, weakening it little by little.

A fracture, total or partial, can be caused by wearing shoes that do not absorb the impact of strides well, or by receiving a direct blow to the bone after a fall during a run. This will result in a lot of pain, especially when trying to support the leg for walking, and quite pronounced swelling. To recover you will need to immobilise the limb and wait several weeks for the crack to heal completely.

Fibula fracture

The fibula is the second bone that makes up the calf along with the tibia, and is attached to the ankle on the outside of the joint. This area accumulates a lot of stress due to the impact to which the runner's leg is subjected with each step during a race, and can therefore fracture.

Fibular fractures are classified into 3 levels; type A, when it occurs only in the bone below the shroud without involving the deltoid ligament; type B, when it occurs right at the joint and affects the deltoid; and type C, when it occurs above the joint and damages both the deltoid ligament and the external lateral ligament of the ankle.

Best products for calf running injury recovery

Bestseller

-

2 Calf Compression Sleeve (Green/Navy)

£20,95 -

2 Calf Compression Sleeve (Pink/Bordeaux)

£20,95 -

Microwave Wheat Bag for Back Pain Relief (Extra Large) (Hearts)

£24,95 -

Microwave Wheat Bag for Back Pain Relief (Extra Large) (Oxford)

£24,95 -

Microwave Wheat Bag for Back Pain Relief (Extra Large) (Sport)

£24,95 -

Microwaveable Wheat Bag for Pain Relief (Hearts)

£20,95 -

Microwaveable Wheat Bag for Pain Relief (Oxford)

£20,95 -

Microwaveable Wheat Bag for Pain Relief (Sport)

£20,95 -

Wheat Bag for Microwave Classic Bottle Shaped (Hearts)

£20,95 -

Wheat Bag for Microwave Classic Bottle Shaped (Oxford)

£20,95 -

Wheat Bag for Microwave Classic Bottle Shaped (Sport)

£20,95

-

2 Calf Compression Sleeve (Black/Gray)

£20,95 -

Foot Massage Roller for Plantar Fasciitis (Black)

£20,95 -

Foot Massage Roller for Plantar Fasciitis (Green)

£20,95 -

Foot Massage Roller for Plantar Fasciitis (Pink)

£20,95 -

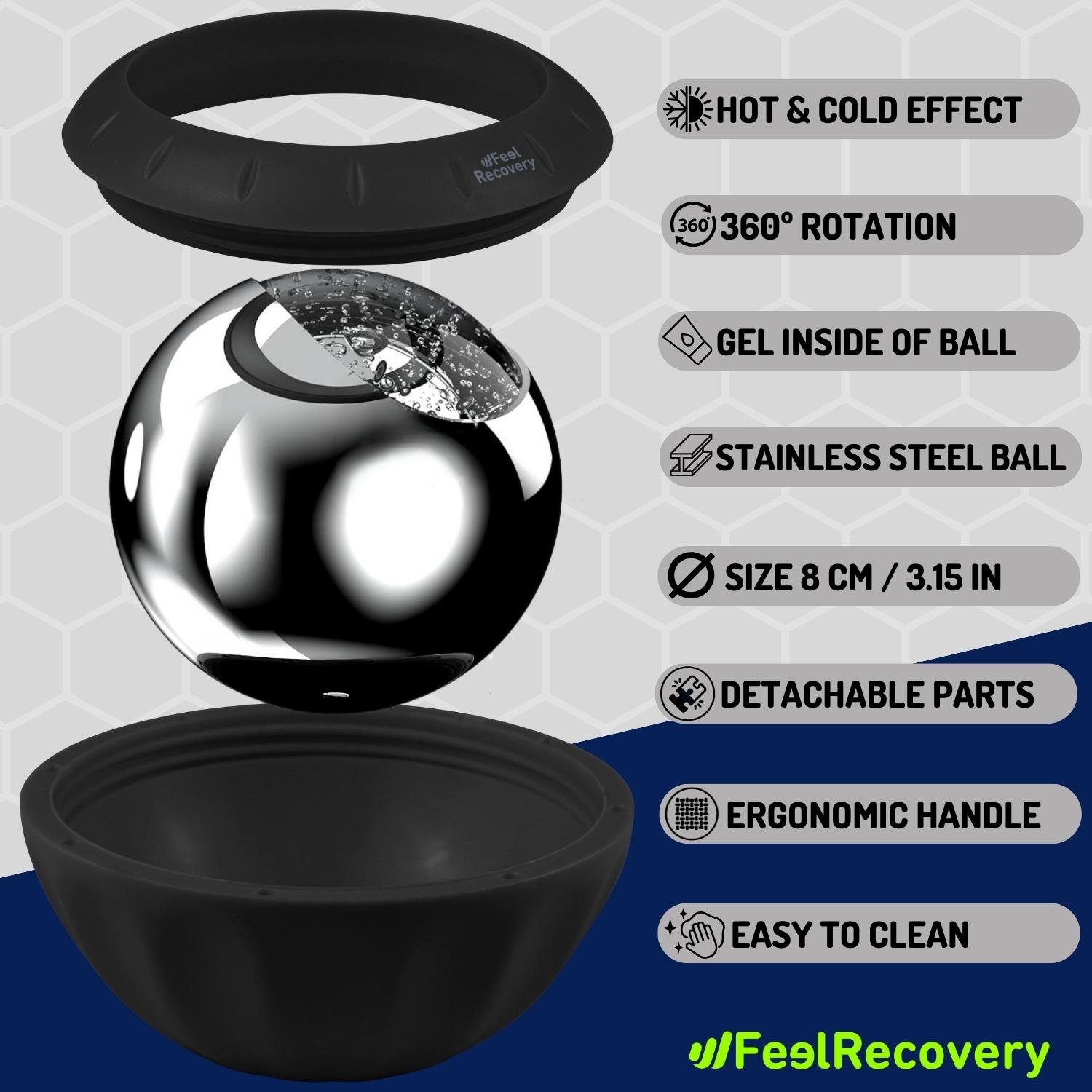

Ice Massage Roller Ball (Black)

£34,95 -

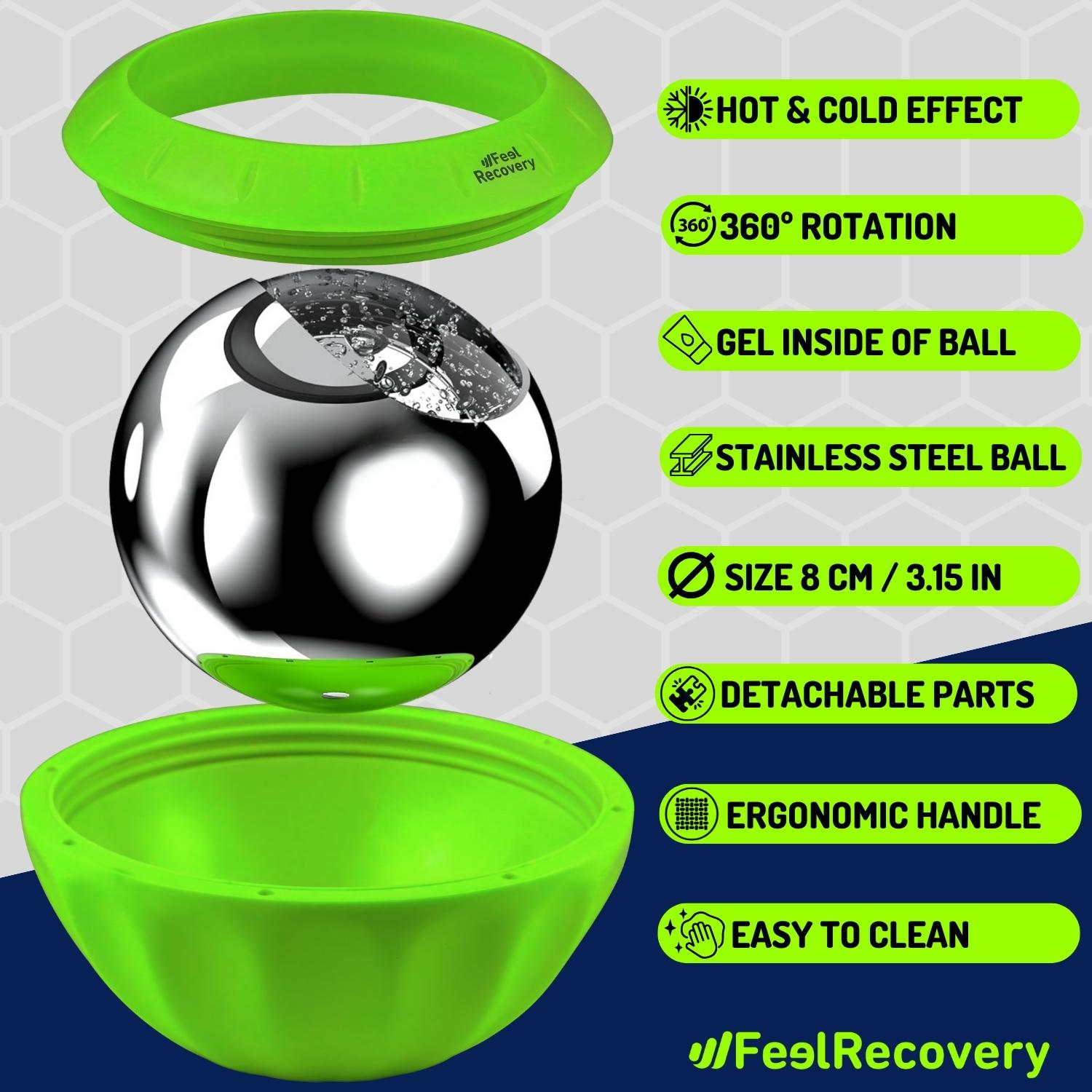

Ice Massage Roller Ball (Green)

£34,95 -

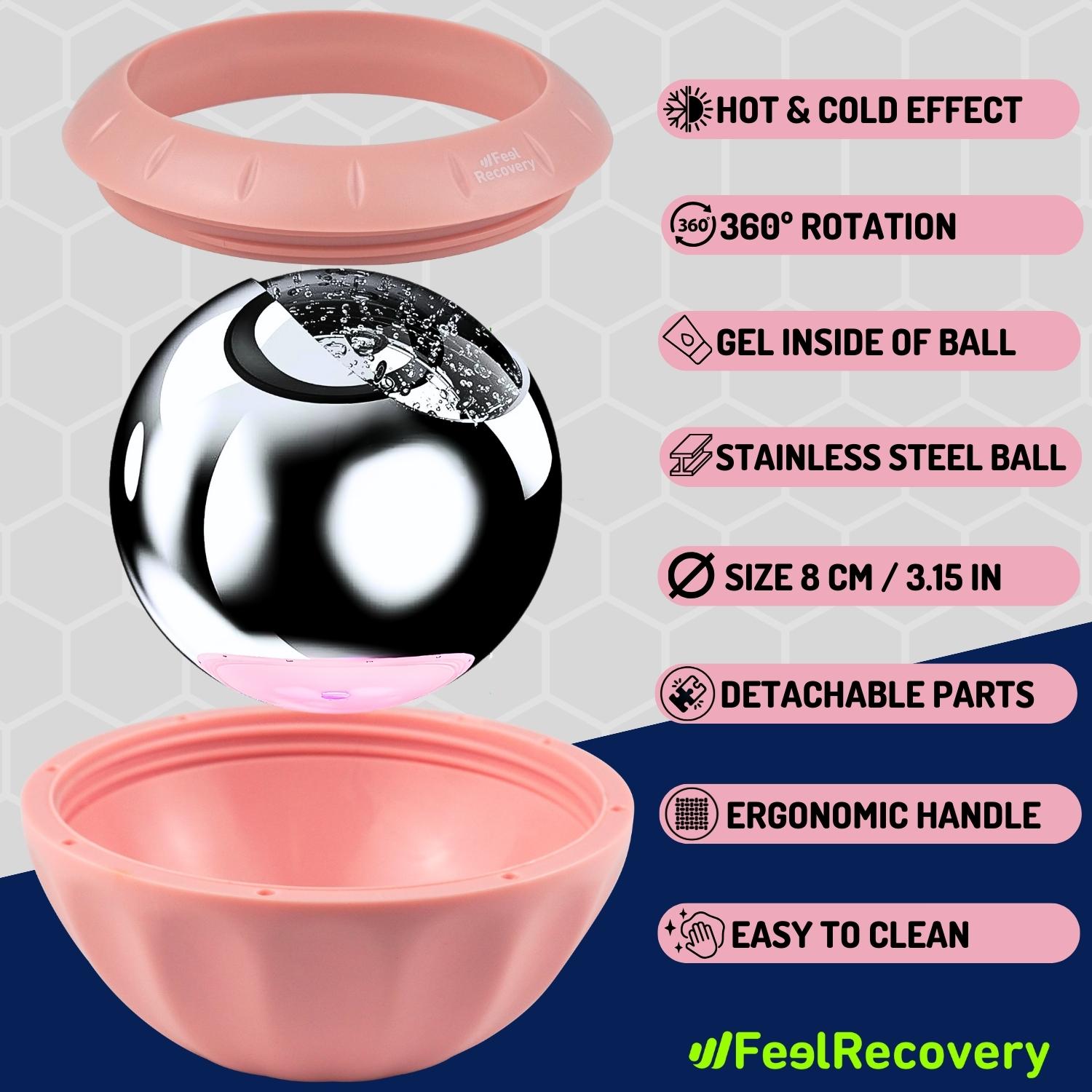

Ice Massage Roller Ball (Pink)

£34,95 -

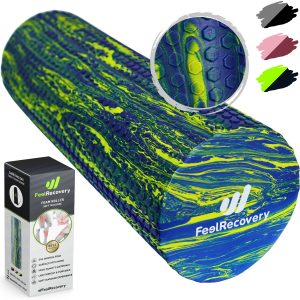

Soft Density Foam Roller for Recovery (Black)

£34,95 -

Soft Density Foam Roller for Recovery (Green)

£34,95 -

Soft Density Foam Roller for Recovery (Pink)

£34,95 -

Sport Compression Socks (1 Pair) (Black/Gray)

£20,95 -

Sport Compression Socks (1 Pair) (Green/Navy)

£20,95 -

Sport Compression Socks (1 Pair) (Pink/Bordeaux)

£20,95

How to apply the RICE therapy to treat calf injuries in runners and athletes?

Except in the case of fractures, the PRICE therapy can be used as a first aid method to mitigate the symptoms of any calf injury. This is an update of RICE created in the late 1970s, and means: protection, rest, ice, compression and elevation, steps that we will show you how to apply below:

- Protection: Protection consists of taking care of the calf so that it does not receive further damage that will negatively affect or make the injury more severe.

- Rest: after securing the calf, the next step is to stop using it and put it in a state of complete rest, so that the cells can begin the recovery process.

- Ice: Ice is used to vasoconstrict the calf muscle fibres so that swelling and pain are reduced as much as possible. Apply ice for the first 48-72 hours.

- Compression: Compression will help keep the swelling from progressing further, which can be achieved with a compression bandage to keep blood flow at bay, or calf braces or compression stockings.

- Elevation: to support the above steps, lie on your stomach and raise your calf above the level of your heart by placing it on a bench, so that gravity causes the blood supply to be reduced.

References

- Fields, K. B., & Rigby, M. D. (2016). Muscular calf injuries in runners. Current sports medicine reports, 15(5), 320-324. https://journals.lww.com/acsm-csmr/fulltext/2016/09000/Muscular_Calf_Injuries_in_Runners.9.aspx

- Bright, J. M., Fields, K. B., & Draper, R. (2017). Ultrasound diagnosis of calf injuries. Sports health, 9(4), 352-355. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1941738117696019

- Alfredson, H., Pietilä, T., Öhberg, L., & Lorentzon, R. (1998). Achilles tendinosis and calf muscle strength. The American journal of sports medicine, 26(2), 166-171. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/03635465980260020301

- Green, B., & Pizzari, T. (2017). Calf muscle strain injuries in sport: a systematic review of risk factors for injury. British journal of sports medicine, 51(16), 1189-1194. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/51/16/1189.abstract

- Garrett Jr, W. E. (1996). Muscle strain injuries. The American journal of sports medicine, 24(6_suppl), S2-S8. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/036354659602406S02

- Arnold, M. J., & Moody, A. L. (2018). Common running injuries: evaluation and management. American family physician, 97(8), 510-516. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2018/0415/p510.html

- van Mechelen, W., Hlobil, H., Kemper, H. C., Voorn, W. J., & de Jongh, H. R. (1993). Prevention of running injuries by warm-up, cool-down, and stretching exercises. The American journal of sports medicine, 21(5), 711-719. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/036354659302100513

- Junior, L. C. H., Costa, L. O. P., & Lopes, A. D. (2013). Previous injuries and some training characteristics predict running-related injuries in recreational runners: a prospective cohort study. Journal of Physiotherapy, 59(4), 263-269. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1836955313702030

- Saragiotto, B. T., Yamato, T. P., Hespanhol Junior, L. C., Rainbow, M. J., Davis, I. S., & Lopes, A. D. (2014). What are the main risk factors for running-related injuries?. Sports medicine, 44, 1153-1163. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-014-0194-6

- Brody, D. M. (1982). Techniques in the evaluation and treatment of the injured runner. The orthopedic clinics of North America, 13(3), 541-558. https://europepmc.org/article/med/6124922